Las estadísticas dicen que cada año decenas de miles de personas ingresan a México sin documentos migratorios, la mayoría provenientes de Honduras. Pero los dígitos no explican las razones del éxodo, de la miseria y la violencia que literalmente se respira en sus países de origen. Para quienes se fueron de allí y los que alistan su partida, la ausencia de futuro no deja opciones: quedarse a morir despacio, o jugarse la vida en un viaje al infierno.

Progreso, Honduras.- José Luis se coloca su prótesis en la pierna, se pone su camisa de solo una manga y se enreda un paliacate en el único dedo de la única mano que le quedó aquel día, en el desierto mexicano.

Abre la puerta, cruza la obra negra que, afirma, un día será su hogar de hombre casado y sale a la calle a buscar a una familia que tenga una historia de migración para contar. Como presidente de la Asociación de Migrantes Retornados con Discapacidad, tiene un notable interés en conocer y dar a conocer todos los casos de migración forzada de su tierra y se ofrece como guía para conocerlos.

A José Luis lo conocen bien en esta ciudad, desde hace muchos años. Primero, por su talento para cantar canciones rancheras y religiosas, y después porque hace 8 años perdió un brazo, una pierna y cuatro dedos cuando cayó de un tren de carga en su segundo intento por llegar a Estados Unidos como migrante sin papeles legales. Fue así que, al volver a Progreso, se involucró en acompañar a quienes vivieron lo mismo que él.

Honduras, su país, es el principal expulsor de migrantes en Centroamérica hacia el norte del continente, que es el flujo migratorio de mayor costo humano en el mundo, y Progreso, su ciudad, es en esta nación una de las principales maquiladoras de mano de obra dispuesta a emprender el viaje.

El viaje al norte parece estar en todas partes, sobre todo en los sitios donde inicia el éxodo. Los autobuses estacionados en la rústica terminal del centro de la ciudad salen cada que los choferes y los ayudantes juntan el pasaje suficiente. Los primeros en partir son los que van a San Pedro Sula, el punto de arranque para abandonar el país. Después, cuando se internen en México, vendrá la región de los asesinatos, accidentes mortales, secuestros y desapariciones.

La región donde ocurre lo que el Movimiento Migrante Mesoamericano llama “genocidio migrante”.

Antes de 1998, cuando el huracán Mitch destruyó los cimientos de Honduras, Progreso era un polo de atracción de trabajadores que llegaban del sur del país a la industria bananera y a las maquilas. Hoy, sus calles son una estampa de lo que la migración forzada da y quita: casas construidas con material, pero con familias fracturadas; pequeños negocios comerciales y restaurantes de comida rápida que se mezclan con las costumbres de este lugar; locales de recepción de remesas como Western Union que se levantan como emporios minando el ahorro de los migrantes.

Al caminar por las calles de Progreso, uno encuentra los puestos de la telefónica Claro (propiedad del magnate mexicano Carlos Slim) llenos de clientes reclamando por el mal servicio; más allá, en las polvorientas colonias de la periferia los habitantes esquivan la oscuridad de la noche al salir de sus trabajos para evitar los asaltos. Jornaleros de las últimas fincas bananeras, obreros del parque industrial, taxistas, oficinistas, desempleados, todos ellos vinculados de alguna manera a la migración.

“La mayoría fueron o serán migrantes”, explica Javier, un trabajador de maquila.

Junto a él, su nieto Anthony de 11 años pregunta “¿Honduras es Bonito?”, y él mismo se contesta que no porque “cualquiera te saca una pistola”.

A Anthony no le sirve que le recuerden todas las bellezas naturales de su país. Ni las ruinas de Copán, ni el mar caribeño de Puerto Cortés, ni las maravillas del mar en el departamento de Atlántida, ni la impresionante serranía de Santa Bárbara. Él está creciendo en un país que se está desmoronando.

Mientras, a paso seguro, dominando con habilidad la pierna falsa que le cuelga desde la mitad del muslo derecho, José Luis camina bajo el intenso sol hondureño y señala las casas que se construyeron con dólares de las remesas de los migrantes, la principal fuente de ingresos de Honduras.

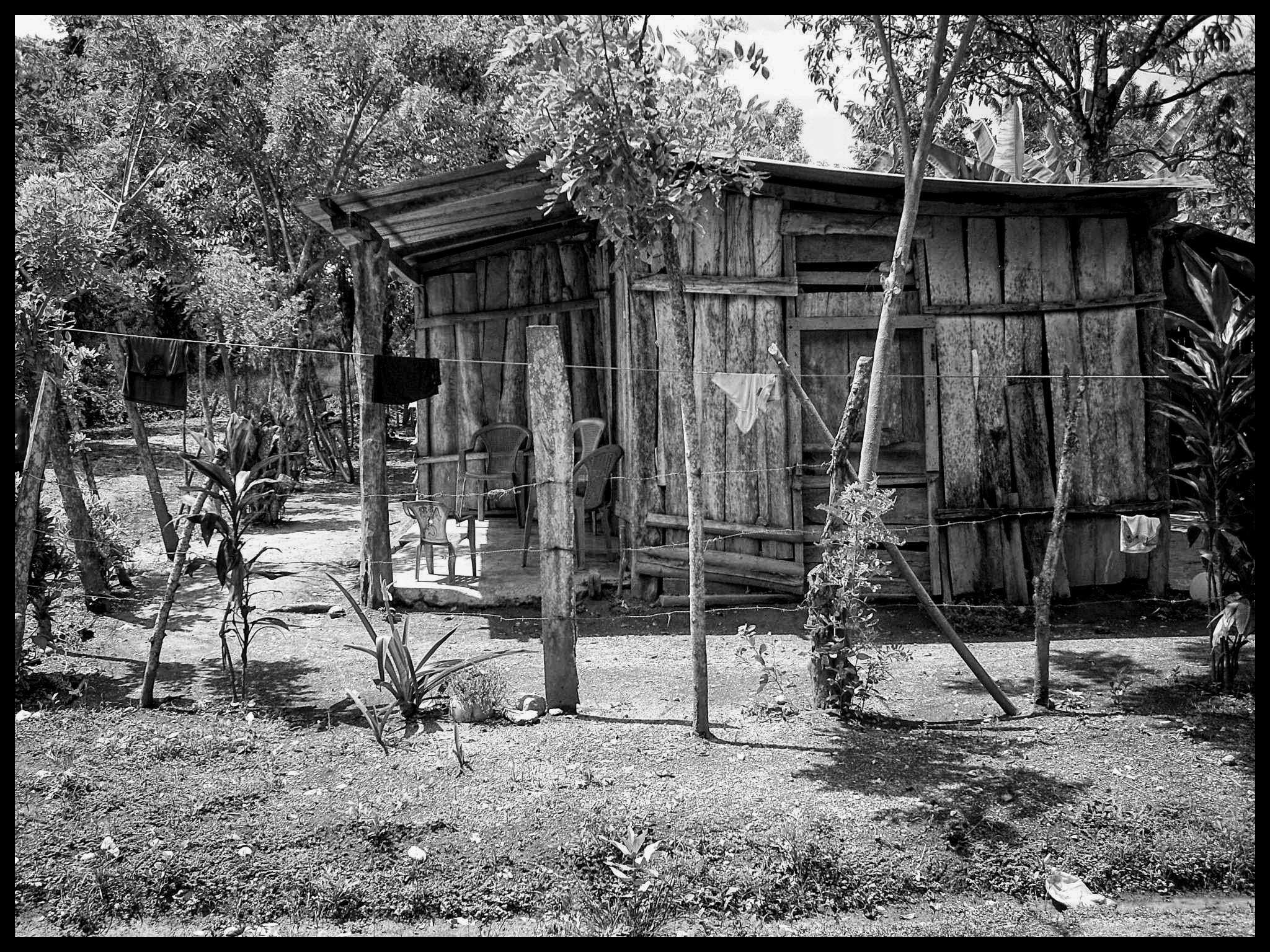

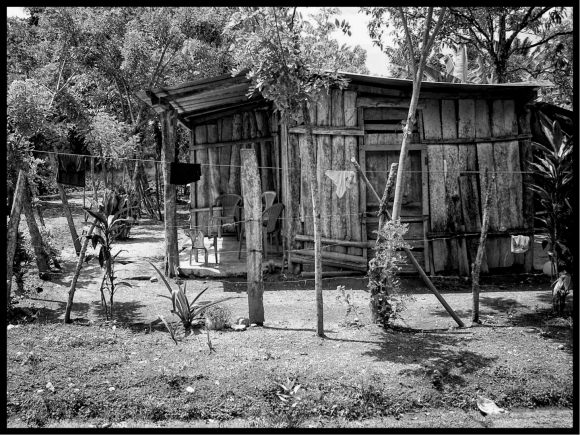

Son casas que se salen del molde, construidas a criterio del dueño. Tienen sus paredes pintadas, espacio para un coche, varias habitaciones y están llenas de protecciones contra ladrones. Cada una representa una historia de supervivencia. A sus ventanas entra más luz.

“Son un montón de casas que las han hecho gracias a las remesas de los migrantes que arriesgan su vida en ese camino. Aquí en Progreso, y en especial en esta colonia es donde está la mera raíz de la migración, donde hay hijos huérfanos porque sus papás se fueron y hay bastante desintegración familiar por causa de la migración”, cuenta José Luis.

En la misma cuadra hay otras casas que son unos cuadritos de concreto con techos de lámina de dos aguas, obra del gobierno nacional de Honduras como parte de un programa social de vivienda. Son los hogares sin alguien que les envíen remesas.

En una de esas casitas vive Karla, de 17 años, que todavía no se va.

Todavía.

EL PAIS QUE FUE

Guido Eguiguren, sociólogo de la Asociación de Jueces por la Democracia, dedicado a la defensa de derechos humanos en Honduras, explica la migración forzada en su país a partir del huracán Mitch, en octubre de 1998.

“El huracán no solo destruyó físicamente al país, a la infraestructura, a miles de vidas. También mostró hacia el mundo un país que no se conocía, con un nivel de desigualdad impresionante y olvidado por el mundo de la cooperación. Un país que se recordaba por el papel nefasto que jugó en la década de los 80 en la región sirviendo como portaaviones de los Estados Unidos”.

Mientras El Salvador y Nicaragua se batían en sus guerras civiles, Honduras prestaba su territorio para entrenar a las fuerzas armadas de los gobiernos de esos países.

Honduras es un país de pobres, el 66.5 por ciento de sus habitantes no tienen ingresos suficientes para alimentarse. Es también un país muy desigual que escupe a personas como José Luis o Karla para buscar su sobrevivencia: el 10 por ciento más rico de la población concentra un ingreso similar a lo que percibe el 80 por ciento de la población de menores ingresos.

Con Guatemala y El Salvador comparte los primeros lugares de expulsión de migrantes a México y los primeros lugares de brecha entre ricos y pobres. Honduras el tercer lugar, Guatemala el cuarto y El Salvador el séptimo lugar.

No se sabe con certeza cuántos hondureños dejan su país cada año, es un dato que el gobierno se resiste a abordar. La cifra aproximada la da la Pastoral de Movilidad Humana de la Iglesia Católica y resulta de contar el número de deportados desde México y Estados: en el 2013 fueron 72 mil hondureños, incluidos niños y bebés.

De lunes a viernes los deportados llegan en dos vuelos diarios al Centro de Atención al Migrante Retornado (CAMR) del aeropuerto de San Pedro Sula, a 30 kilómetros de Progreso. De los aviones descienden hombres y mujeres que se fueron libres y regresan amarrados de pies, cintura y muñecas con cadenas y con un costal semivacío como único equipaje.

Al bajar del avión caminan unos pasos, miran a varios lados y salen de la terminal aérea. En pocos días, quizá en ese mismo momento, emprenden el camino de regreso. Y comienzan de cero.

José Luis, quien habitualmente es un parlanchín, guarda silencio cuando los mira llegar, recién desamarrados y agradecidos con su país los recibe con una “baleada”, una simple tortilla de harina embarrada de frijoles.

Es un choque brutal con la realidad. A su regreso son más pobres, más vulnerables y más expuestos a la violencia que cuando dejaron su patria.

EL PAIS QUE ES

José Luis vive a una calle de la colonia San Jorge, un barrio fundado por misioneros jesuitas a principios de la década pasada después de que el huracán Mitch se “estacionó” un día y medio sobre Honduras y arrojó agua y viento con la fuerza de un meteoro categoría cinco, el nivel más furioso de todos.

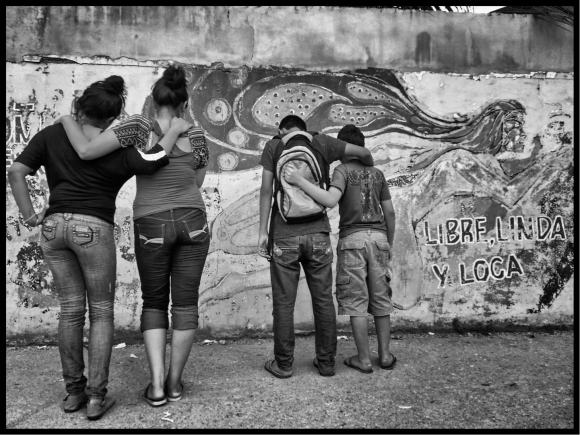

Hoy, San Jorge está controlado por dos “banderistas” (espías) de la Mara Salvatrucha que informan a sus jefes quién entra y quién sale. Sus cuatro entradas son vigiladas por los “güirros”, unos muchachitos reclutados por los mareros y armados con pistolas que asustan a cualquiera. Desde cerro arriba, atrás de la cortina imaginaria que marca el límite del barrio, llegan las órdenes operativas del hampa que se extiende en Progreso.

Manuel de Jesús Suárez, promotor social del Equipo de Reflexión, Investigación y Comunicación, una organización que intenta entender y las causas de la migración en Honduras, habla de este país que ahora es.

ntes la migración era para escapar de la pobreza. Hoy también es una forma de salvar la vida, escapar de la violencia cotidiana y permanente en cada calle, barrio, casa, gobierno de Honduras.

“Las causas de la migración no son coyunturales sino estructurales, es decir, la falta de trabajo y salario dignos, el acceso a la salud, a la educación, a la vivienda. Ahora otro fenómeno es la violencia, el crimen organizado, la narcoactividad van formando parte de la estructura de país. Las causas se han enquistado en el sistema, están ahí. Esto origina que la mayoría de hombres y mujeres más empobrecidos quedan excluidos del sistema, por tanto, se van”, explica.

Manuel de Jesús, hombre que pasa los 50 años, conoce bien la historia. Nació en Progreso y ha visto el derrumbe de las maquilas y las bananeras, así como la llegada de las cadenas de fast food norteamericanas que avientan su olor a grasa a las caóticas calles del corazón de su ciudad. Las sucursales de Wendys, Burguer King y Pizza Hut tienen vigilantes armados con escopetas dentro de sus locales.

En 2013, 9 mil 453 personas murieron en Honduras por “causas externas”, es decir, víctimas de la violencia. El 71.5 por ciento de ellas fueron asesinadas. En este país que libra una guerra no declarada cada mes matan a 563 personas, 19 cada día.

Por estos números Honduras es el país con la mayor tasa de homicidios en el mundo.

EL DESPOJO Y EL ABANDONO

José Luis camina por las calles de Progreso con maestría sobre su única pierna y desde las ventanas de las casas se alcanza a escuchar el sonido de un aparato radiofónico. La estación Radio Progreso fundada por jesuitas recoge los problemas laborales y de violencia de los comuneros, del sistema educativo, de derechos humanos y de migración con su programa de los domingos que sirve de catarsis para el abandono.

La señal que se escucha desde esas ventanas bien puede hacer de compañía de las personas que quedan en las familias rotas. Un migrante entra al aire para contar que, cuando se fue de Honduras, “otro gallo le echó plumas a su mujer” y se quedó sin esposa. Las llamadas siguen entrando. En su mayoría, son radioescuchas que viven o vivieron alguna consecuencia de la migración forzada.

Las conductoras del programa dominical son Rosa Nelly Santos y Marcia Martínez, integrantes del Comité de Familiares de Migrantes Desaparecidos (Cofamipro), y en esta ocasión hablan de desintegración familiar. Antes de ir a un corte en el programa, Rosa Nelly presenta la melodía Hermano Migrante, de Natividad Herrera que canta: “Vuélvete pronto y goza con los tuyos / olvida el llanto y todo ese dolor”.

Volver a la patria, repoblar los pueblos a quienes la migración al norte les arrebató a su gente. Progreso, como muchas comunidades y barrios de Centroamérica, se vacía paulatinamente desde hace varios años. Atrás quedan las casas, a veces solitarias, la mayor parte habitadas a medias.

Detrás de cada puerta y ventana hay historias fracturadas.

LA VIDA MUTILADA

Corría el año 2005, era el segundo intento de José Luis de ir a Estados Unidos. Él y su amigo Selvi tardaron en llegar al norte de México 19 días que transcurrieron en calma. Viajaron desde Progreso sin parar. Tomaron el tren en Tapachula. Llegaron al estado de Chihuahua porque cruzarían la frontera Ciudad Juárez-El Paso.

Para José Luis, el éxito del viaje consistía en no dejar que su amigo se durmiera sobre el tren. Lo molestaba, le hablaba, lo hacía enojar y le daba de patadas. No quería que él se durmiera.

José Luis –buen futbolista, guitarrista y aficionado a pescar en el río Ulúa que bordea Progreso- se sentó al lado de los engranajes de los vagones y se inclinó al frente hacia sus pies para amarrarse un zapato. Cosa rara: el sudor le cubría toda la nuca hasta la coronilla. Nunca había estado en el desierto. El tren se adentraba a la ciudad de Delicias y José Luis Pestañeó.

“De repente quedé a oscuras y me caí, fue un desmayo por el calor seco que hace ahí en junio. El tren me cortó una pierna. Después metí el brazo al no poder sacar mi pierna y también me lo cortó. Después metí el otro brazo y me lo aplastó la rueda del tren”.

Su amigo Silvi no se dio cuenta hasta que, kilómetros adelante, notó que las ruedas del tren estaban pintadas de sangre. Lo creyó muerto. Ahora él vive en Estados Unidos donde creó una familia. En el sur se quedó su amigo, el que le cuidó en el lomo del tren y quien ahora se mueve sobre una pierna y balancea por las calles el brazo que le perdonó La Bestia.

Se autoriza su reproducción siempre y cuando se cite claramente al autor y la siguiente frase: “Este trabajo forma parte del proyecto En el Camino, realizado por la Red de Periodistas de a Pie con el apoyo de Open Society Foundations. Conoce más del proyecto aquí: enelcamino.periodistasdeapie.org.mx”

What lies behind the numbers of tens of thousands of migrants who cross the border each year? Statistics suggest that people in their tens of thousands cross into Mexico without migratory documents, mostly from Honduras. But these figures don’t explain the reasons behind the exodus, for the misery and violence that permeate their countries of origin. For those who have left, and for those about to leave, the absence of the future leaves them with few options: stay to die a slow death, or risk their lives in a hellish journey.

Progreso, Honduras.- José Luis places his artificial limb on his leg, puts on his shirt with only one sleeve, and places a bandana around the only finger on the only hand he still has from that day in the Mexican desert.

He opens the door, passes the ongoing construction site that one day, he says, will house his family when he is married, and goes out into the street in search of a family that has a story of migration to tell him. He is president of the Association of Migrant Returnees with a Disability (Asociación de Migrantes Retornados con Discapacidad), and he has a remarkable interest in familiarizing himself with all the cases of forced migration from his country; he offers himself as a guide to know their stories.

For many years, José Luis has been well known in this city. Famous at one time for his talent singing rancheros and religious songs, eight years ago he lost his arm, a leg, and four fingers when he fell from a cargo train. It was his second attempt to reach the United States as an undocumented migrant. That’s who he was when he came back to Progreso and so he became involved in accompanying those who experienced the same thing he had lived through.

Honduras, his country, is the place most Central American migrants leave to go north. The flow of migration from Honduras has the greatest human cost in the world. Progreso, his city, is one of Honduras’s principal manufacturers of manpower ready to undertake the journey.

The journey north seems to be everywhere but above all else in those places where the exodus begins. When the drivers and their helpers have enough passengers, the buses parked in the city’s dilapidated central bus station can leave. The first buses to go are those for San Pedro Sula, a good place to leave the country. Then, when they enter Mexico, they are in the land of murders, fatal accidents, kidnappings and disappearances.

The Mesoamerican Migrant Movement labels the region the place of “migrant genocide.”

Before 1998, when Hurricane Mitch destroyed Honduras, Progreso was a place that attracted workers from the country’s south because of its banana industry and its factories. Today, its streets bear the marks of what forced migration gives and takes: houses constructed from material but with fractured families; small businesses and fast food restaurants that mingle with this place’s customs; places to receive Western Union remittances that spring up like businesses mining migrants’ savings.

A walk around Progreso’s streets and one finds Claro telephone stalls belonging to Mexican business magnate, Carlos Slim, and brimming with clients complaining about the poor service. Further on, in the dusty peripheral neighborhoods, residents leaving work avoid the darkness so they won’t be assaulted. Day laborers from the last of the banana plantations, industrial workers, taxis, office workers, and the unemployed – all of them are somehow linked to migration.

“Most of them were, or will be, migrants,” says Javier, a factory worker.

His eleven year-old grandson Anthony is with him and asks, “Is Honduras beautiful?” He replies that it’s not because “anybody can pull a pistol on you.”

It won’t do anything for Anthony to remember all the beautiful things about his country. Neither the Copán ruins, nor the Caribbean port of Puerto Cortés, nor the marvels of the sea around Atlántido, and not even the impressive mountain ranges of Santa Bárbara. He is growing up in a crumbling country.

Meanwhile, surefooted, and dextrously dominating his prosthetic leg that hangs halfway down his right thigh, José Luis walks under the intense Honduran sun, pointing at the houses built with dollars from migrants’ remittances, the country’s principle source of income.

They are houses that break the mold, built according to their owner’s criteria. They have painted walls, space for a car, for several rooms and they are covered with anti-theft devices. Each house represents a survival story. More light enters their windows.

“There are a ton of houses built thanks to migrants’ remittances, those who risk their lives on the journey. Here in Progreso, and especially in this neighborhood are the roots of migration, where there are orphans because parents left and there’s significant family disintegration because of migration,” says José Luis.

In the same block there are other houses that are concrete blocks with plastic roofs, built by Honduras’s government through its social housing program. These are the homes where nobody sends back remittances.

Karla lives in one of these houses. She’s seventeen years old. She still hasn’t left.

Yet.

THE COUNTRY THAT WAS

Guido Eguiguren, a sociologist from the Association of Judges for Democracy (Asociación de Jueces por la Democracia), a Honduran human rights defender, explains forced migration in his country taking place after Hurricane Mitch, in October 1998.

“The hurricane didn’t just physically destroy the country, its infrastructure, and thousands of lives. It also showed the world a country it barely knew, with a staggering level of inequality, a country forgotten by the world of development and cooperation. A country known for the nasty role it played in the 1980s acting as the United States’ aircraft carrier.”

While El Salvador and Nicaragua were battered by civil war, Honduras lent its territory to train the armed forces of the governments of those countries.

Honduras is a country of poor people where 66.5 percent of its residents do not have sufficient income to feed themselves. It’s also an unequal country that spits on people like José Luis or Karla as they look for ways to survive: 10 percent of the richest people in the country have an income equal to that of 80 percent of its low-income population.

Honduras shares first place with Guatemala and El Salvador for pushing out migrants to Mexico, and it takes first place in the divide between rich and poor. In terms of inequality in the Latin American region, Honduras take third place, Guatemala is in fourth, and El Salvador comes in at number seven.

Nobody knows for certain how many Hondurans leave their country each year, and it’s a figure that the government does not want to give out. The rough estimate by the Catholic Church’s Pastoral for Human Movement comes from counting the numbers of people deported from Mexico and the United States: in 2013 it was 72,000 Hondurans, including children and babies.

From Monday to Friday, deportees arrive in two airplanes every day at the Center for Returnee Migrants (Centro de Atención al Migrante Retornado, CMAR) at the San Pedro Sula airport, 30 kilometers from Progreso. Men and women get off the planes who left the country free and who come back with their feet bound in tape, their wrists in chains, and with a half-empty sack as their only baggage.

They walk a few steps on leaving the plane, look around from side to side and leave the airport terminal. In a few days, maybe at that very moment, they will undertake the journey back, starting from scratch.

José Luis, who is normally a chatterbox, keeps silent when he sees them arrive, recently unbound and thankful that their country greets them with a “baleada,” a meager flour tortilla covered in beans.

It’s a brutal brush with reality. When they return they are even poorer, more vulnerable, and more exposed to the violence that forced them to flee in the first place.

THE COUNTRY THAT IS

José Luis lives in a street in the San Jorge neighborhood, a barrio established by Jesuit missionaries at the beginning of the last decade after Hurricane Mitch “positioned” itself for a day and a half over Honduras, inundating the country with the water and wind of a category five hurricane, the most furious of them all.

Today San Jorge is controlled by two spies (“banderistas”) of the Mara Salvatrucha who report to their bosses who comes and goes. Its four entrances are guarded by the “güirros”, some young men recruited by the Maras and armed with pistols that scare everybody. Instructions from the underworld that extend throughout Progreso come from the hill above, behind an imaginary curtain that marks the barrios’ borders.

Manuel de Jesús Suárez, communications officer of the team of Reflection, Investigation and Communication, an organization that tries to understand the causes of migration from Honduras speaks about the country it is now.

Previously, migration used to occur as an escape from poverty. Today it is a way of saving one’s life, escaping from the daily violence that is permanently in the street, house, and in the Honduran government.

“The causes of migration are not conjunctural but structural, meaning the lack of work and decent salaries, access to health, to education, to housing. Now the other phenomenon is violence, organized crime, and the drug business shaping the country’s structure. The causes are a cyst in the system. They are there. The system makes it so that the majority of the poorest men and women remain excluded and so they leave,” he explains.

Manuel de Jesús, a man of more than 50 years old, knows this history well. He was born in Progreso and he has seen the collapse of the factories and the banana plantations, along with the arrival of the U.S. fast food outlets that spew out their greasy odor in the chaotic streets at the heart of the city. Wendy’s outlets, Burger Kings and Pizza Huts – all have armed guards with shotguns stationed inside their branches.

In 2013, 9,453 people died in Honduras for “external reasons”, meaning they were victims of violence. Of these 71.5 percent were murdered. In this country where an undeclared war rages, 563 people die each month. That’s nineteen deaths every day.

These numbers mark Honduras with the highest homicide rate in the world.

DISPOSSESSION AND DERELICTION

José Luis walks Progreso’s streets with mastery on his only leg. The sounds of radios drift from the windows of houses. Radio Progreso was established by Jesuits. On a Sunday program serving as catharsis to confront the abandonment, the station covers work problems, neighborhood violence, the educational system, human rights and migration.

The signal that can be heard from these windows accompanies people whose families have been broken. A migrant comes on the air to tell how, when he left Honduras, “another cock feathered his wife” and his wife left him. The calls keep on coming. Mostly on the radio one hears about those who live or lived with some consequence of forced migration.

The presenters on the Sunday program are Rosa Nelly Santos and Marcia Martínez, members of the Committee of Relatives of Disappeared Migrants (Cofamipro), and on this occasion they are talking about family disintegration. Before moving to a break in the program, Rosa Nelly announced the tune Hermano Migrante (Fellow Migrant) by Natividad Herrera who sings, “Return soon and enjoy what’s yours / forget the crying and all that pain.”

Return home; fill the towns with people that migration took north. Progreso, like many communities and barrios in Central America has been slowly emptied in the past year. Houses remain behind, sometimes empty, but most half inhabited.

Behind every door and window lie fractured stories.

LIFE, MUTILATED

The year was 2005, and it was José Luis’s second attempt at going to the United States. He and his friend Selvi took nineteen days to reach northern Mexico; those days were uneventful. They traveled from Progreso without stopping. They took the train in Tapachula, Mexico. They arrived in Chihuahua. They were going to cross the border at Ciudad Juárez-El Paso.

For José Luis, the success of the journey consisted in not leaving his friend while he slept on the train. He annoyed him. He spoke to him. He made him angry and he kicked him. He didn’t want him to fall asleep.

José Luis – a good footballer, guitar player, and fan of fishing in the Ulúa River bordering Progreso – sat beside the train wagon’s gears and stretched forward to tie a shoe. Strange thing: sweat covered the whole of his neck to the top of his head. He had never been in the desert. The train entered the city of Delicias and José Luis blinked.

“Suddenly things went dark and I fell. I fainted from the dry, June heat. The train severed my leg. Then I put out my arm because I couldn’t free my leg and it cut that off, too. I put out my other arm and the train wheel squashed it.

Silvi, his friend, did not realize what had happened until kilometers further on when he noticed blood covering the train wheels. He thought he was dead. He now lives in the United States where he has started a family. In the south, his friend remained behind: the man who took care of him on the train and who now moves around the streets on one leg, balancing on the arm left him by La Bestia.

This story is part of a series produced by En El Camino by Periodistas de a Pie, and funded by the Open Society Foundations. It has been translated pro bono, and without permission, by the Mexican Journalism Translation Project.

Translation into English: Patrick Timmons, for the MxJTP

Is a human rights investigator, historian, and journalist. Follow his activities on Twitter @patricktimmons. Timmons has publications — translations, articles, or reviews — in the Tico Times (Costa Rica), El País in English (Spain), CounterPunch (USA), The Texas Observer (USA), The Latin American Research Review (USA & Canada), and the Radical History Review (USA). A graduate of the London School of Economics and Political Science (1996), Timmons holds three advanced university degrees: a Master’s in Latin American Studies from the University of Cambridge, UK (1998); a Ph.D. in Latin American History from the University of Texas at Austin, USA (2004); and, a Master’s in International Human Rights Law from the University of Essex, UK (2013).