[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

En los últimos años el gobierno mexicano ha presumido los numerosos rescates de migrantes. En la práctica, éstos terminan en deportaciones masivas pues no se garantiza su derecho a la justicia y a la seguridad. Prueba de ello es que menos del 1 por ciento de los supuestos rescatados en el 2014, obtuvo su visa humanitaria.

Por: Mely Arellano, Ximena Natera, Jade Ramírez y Majo Siscar

Cuando la secuestraron, Paola Quiñones no se comunicó con su familia. Tampoco con la policía u otra autoridad. Al primer lugar al que llamó fue al albergue para migrantes Hermanos en el Camino, que dirige el padre Alejandro Solalinde en Ixtepec, Oaxaca. Sus secuestradores pedían un rescate cuantioso por cada uno de los migrantes que dormían hacinados en varias casas de seguridad, pero el sacerdote logró que en lugar del pago llegase un operativo policial a liberarlos.

La madrugada del 23 de junio de 2014 amaneció de golpe en Reynosa. La Procuraduría General de la República mandó catear casas, según las señas dadas por Paola Quiñones, hasta dar con más de un centenar de migrantes, 114 según los defensores de derechos humanos, entre ellos Paola Quiñones y su compañero de viaje, Jorge Moncada.

Ambos llevaban ya 11 días encerrados, después que hubiesen sido bajados a punta de pistola del autobús en el que viajaban, rumbo a la frontera de Tamaulipas y Texas. Ese 23 de junio los trasladaron a la Procuraduría de Justicia de Tamaulipas para rendir declaración junto a los otros 112 migrantes. Pasaron la noche allí, sin una colchoneta donde dormir, siquiera una cobija. Al día siguiente se los llevaron hasta la Procuraduría General de la República, en la capital mexicana, donde pasaron otros tres días. Luego los llevaron a la estación migratoria Las Agujas, en Iztapalapa, al oriente de la Ciudad de México, donde empezarían los trámites para sacarlos del país, sin recibir atención de ningún tipo.

Casi todos los migrantes fueron deportados en los días siguientes.

Los migrantes que han sido víctimas de un delito en México tienen el derecho a denunciar e iniciar el proceso que regularice su estancia en el país a través de la visa por razones humanitarias o el refugio, como señalan las leyes de Migración y sobre Refugiados y Asilo político.

Sin embargo, en la práctica el gobierno mexicano que encabeza Enrique Peña Nieto viola su propia ley y los anunciados “rescates” de migrantes terminan, en realidad, en deportaciones masivas y en violaciones a sus derechos de acceso a la justicia y a la seguridad.

En esta investigación realizada por En el Camino a partir de peticiones de información, seguimiento a casos de secuestro y entrevistas con defensores de migrantes, se refleja algo que las organizaciones han bautizado como “detenciones enmascaradas”, pues las cifras de migrantes que supuestamente fueron rescatados coincide con el número de deportados, además que menos del 1 por ciento de los migrantes “rescatados” en el año 2014, obtuvo su visa humanitaria.

¿RESCATES O DEPORTACIONES?

Ni la ley ni el reglamento de Migración define el término“rescate” o “rescatado”. Sin embargo, en sus boletines el INM lo utiliza para señalar que se liberó a migrantes de manos de traficantes, secuestradores o casas de seguridad o tráilers donde estaban en espera de cruzar a Estados Unidos.

La falta de acatamiento de la ley y del seguimiento jurídico a los migrantes “rescatados” impide distinguir cuándo se trata de migrantes que realmente estaban secuestrados y cuándo de quienes esperaban en casas de seguridad, hoteles o a bordo de camiones cruzar la frontera.

“(En algunos casos) Parece que la autoridad está engañando y en realidad está deteniendo a migrantes que esperan cruzar” alerta Córdova, desde el Consejo Ciudadano del INM.

El 11 de junio, cuando se subió a aquel autobús hacia la frontera entre Tamaulipas y Estados Unidos Paola no pensaba que le pudiera pasar nada. Esa vez viajaba de manera regular, por una ruta oficial alejada de la vulnerabilidad de los escondites por los que tienen que cruzar los indocumentados. Pero el crimen no entiende de documentos.

Diez días después del operativo en Reynosa, Paola y Jorge lograron salir de la estación migratoria y se establecieron en el Centro de Acogida y Formación para Mujeres Migrantes y sus Familias (Cafemin), el albergue dirigido por la Congregación de las Hermanas Scalabrinianas. Desde allí iniciaron la denuncia formal por el secuestro. Lo pudieron hacer gracias al acompañamiento de una institución independiente del Estado.

Los otros 112, asegurados por la PGR y en custodia del INM se quedaron detenidos en la estación y uno por uno fueron devueltos a sus países, luego de firmar una salida que las autoridades llaman “voluntaria”. Legalmente se conoce como “retorno asistido”, pero en la práctica es igual que una deportación solo que no queda registrada en el expediente migratorio del indocumentado.

Alguien que acaba de pasar por un trauma necesita un lugar dónde recuperarse, asistencia psicológica, legal y médica. Pero los retornos asistidos se fincan en el desgaste, desatención psicológica y anulación de esperanza de las víctimas que no encuentran un acceso firme a la justicia o una liberación rápida para continuar con su objetivo de llegar a la frontera norte.

“No hubo ni una sola denuncia proveniente de los migrantes en custodia del INM, este los desesperó y dio largas para evitar que iniciaran un proceso legal de regularización. Los orilló a firmar su salida”, sostiene Alberto Donis.

“Les desaniman, les dicen: usted va a estar detenida mientras dure todo el trámite, así que mejor váyase, váyase, le vamos a pagar el autobús, le van a dar de comer, mejor regrésese. Esa actitud es de todos los días”, explica Leticia Gutiérrez, directora de Scalabrinianas Misión para Migrantes y Refugiados, más conocida como la Hermana Lety, y que en el último año ha fungido como mediadora entre organizaciones civiles y la PGR en cuestión de migrantes víctimas del delito.

VICTIMAS SIN VISA HUMANITARIA

Los migrantes tenían derecho a regularizar su estancia en el país por haber sido víctimas de un delito. De hecho, Paola Quiñones ya había empezado a tramitar su regularización cuando llegó por primera vez al albergue del padre Solalinde. Apenas unos meses antes, en Tuxtla Gutiérrez, la capital de Chiapas, tres policías municipales la violentaron y le robaron todo su dinero y pertenencias bajo la amenaza de llevarla a una oficina del INM. Cuando al fin consiguió llegar a Ixtepec, el sacerdote y Donis la animaron a denunciar. Acusación en mano, comenzó a gestionar la visa.

En el Camino pidió vía el sistema Infomex “el detalle de operativos de rescate, salvamento, liberación y/o aseguramiento de migrantes del 1 de enero de 2008 hasta febrero de 2015”. La información se entregó a partir del año 2012, cuando empezó a ser vigente la nueva Ley de Migración.

Desde entonces y hasta febrero de 2015, según los datos oficiales (entregados en la solicitud número 0411100011515), se han realizado 84 mil 005 operativos a través de controles de revisión y verificación en el Distrito Federal y 29 estados de la República (algunos entregaron la información en un formato ilegible o con información incompleta: Aguascalientes, Durango, Veracruz, Baja California Sur y Sinaloa). Entre todos ellos la misma autoridad sólo reconoce a 427 personas como “posibles víctimas del delito”.

Es decir, sólo un migrante en cada 200 operativos de “rescate” habría sido violentado. Las cifras entregadas vía transparencia dejan ver una diferencia brutal entre migrantes “rescatados” y los reconocidos como “víctimas”.

“Si los 127 mil rescatados que menciona Ardelio (Vargas, el comisionado del INM) fueron arrancados de las garras de los delincuentes deberíamos computar miles de visas humanitarias”, reflexiona Córdoba.

Según la hermana Leticia cuando un migrante es víctima de un delito, si bien es cierto que puede decidir no denunciar la mayoría sí lo hace si se les acompaña debidamente. Su organización atendió en los primeros 6 meses de 2015 a 189 víctimas del delito, sólo 10 decidieron no denunciar.

El equipo de En el Camino indagó con el INM cuántas visas humanitarias se han entregado desde 2012 a la fecha, a través del INAI (solicitud número 0411100011515). Sin embargo la autoridad no señaló que se hubieran otorgado.

De la información entregada se desglosa que en 314 casos podría ser que les hubieran dado un oficio de salida. Este es un permiso para salir del país de manera legal en 30 días hábiles. Y usamos el verbo condicional podría porque la misma respuesta viene desglosada por el total de operativos y no por los casos particulares; entonces por ejemplo de un operativo donde “rescataron” a 12 personas hay 3 “posibles víctimas del delito”, pero el INM sólo nos dice qué pasó con las 12 personas, no con las otras 3.

Lo que sí podemos asegurar a partir de los datos es que al menos 113 de esas 427 “posibles” víctimas del delito fueron directamente devueltas a sus países de origen, ya sea vía la deportación o el retorno asistido.

Por su parte, la Unidad de Política Migratoria no registra cuántas visas humanitarias se han dado hasta antes del 2013, pero sí a partir del 2014. Ese año registra que se entregaron 623, una cifra ínfima comparada con los 127 mil 149 migrantes que, según la misma Unidad, fueron rescatados en 2014; es decir se les otorgó visa humanitaria a 0.4 por ciento de los migrantes que habrían sido “rescatados”. Del resto, registra que 107 mil 814 fueron devueltos a sus países de origen y del resto, más de 18 mil casos, no informa nada.

En los primeros seis meses del 2015 se entregaron 527 visas humanitarias, pero se “rescataron” 97 mil 513 y fueron “devueltos” 82 mil 266. El promedio de visas humanitarias entregadas fue también menor al uno por ciento.

SIN ATENCIÓN HUMANITARIA.-

Aquél mes de junio de 2014, después de que los 114 migrantes fueron trasladados a Las Agujas, en Iztapalapa, llegó el padre Alejandro Solalinde y uno de sus colaboradores, Alberto Donis, movilizados ante la llamada de Paola Quiñones. El sacerdote llevó un médico que encontró a Paola y a Jorge con infecciones severas, deshidratados y malnutridos. Ambos estaban frágiles y sufrían estrés postraumático a consecuencia del secuestro.

“Fue muy difícil para mí, no fue el trato que merecíamos y necesitábamos, no hubo asistencia médica, peor psicológica. No sabíamos qué estaba pasando”, relata ahora Quiñones desde Honduras, donde está de visita a su familia.

En Las Agujas, hay habitaciones con rejas, celdas de castigo e incluso una mafia de custodios que controlan un mercado de cigarros, comida o llamadas, según ha denunciado la organización Sin Fronteras. No hay, en cambio, dinero para asegurar los derechos de salud y reparación mínimos que necesita alguien que acaba de sufrir un secuestro u otros delitos graves.

“Estos migrantes, por ley, tenían que estar en albergues especiales y gubernamentales por ser víctimas que están por iniciar un proceso legal. No están en calidad de detenidos, pero los dejaron en la estación sin ningún apoyo ni oportunidad de irse”, explica Alberto Donis, quien junto al Padre Solalinde intentó negociar con las autoridades el traslado de esos 114 migrantes a Ixtepec sin éxito ante la falta de recursos.

El Instituto Nacional de Migración, INM, aseguró a En el Camino en una llamada telefónica al área de comunicación que sí hay un mandato interno para atender a migrantes que quieran acreditar su legal estancia por ser víctimas o testigos del delito y que en este, el Estado mexicano provee la supervivencia y bienestar de los migrantes. Sin embargo según el “Procedimiento para la detección, identificación y atención de personas extranjeras víctimas del delito”, un protocolo de actuación para la autoridad migratoria contenido en el Reglamento de la Ley de Migración sólo establece que a la víctima de delito “se le canalizará a alguna institución pública o privada para recibir la atención que requiera”, y para la víctima del delito de trata de personas “se garantizará su estancia en albergues o instituciones especializadas”.

Pero a Paola Quiñones y al resto de migrantes “rescatados” ninguna institución le ofreció un lugar o un dinero con el que vivir en lo que duraba el trámite. Solo el albergue de Solalinde le permitió quedarse tres meses a cambio de cocinar en el comedor.

Leticia Gutiérrez señala que la falta de seguimiento a las víctimas de delito es tal, que ni siquiera se da seguimiento para obtener patrones y prevenir futuros secuestros.

“El discurso que utiliza migración va dirigido a convencer a la opinión pública pero el mayor problema es que cuando da visas humanitarias, en el 90 por ciento de los casos fue porque desde los albergues acompañan a los migrantes en su proceso. Dentro del Instituto nadie consigue papeles”, cierra Donis.

Mientras las deportaciones y retornos asistidos continúan a diario, la averiguación previa que impulsó el guatemalteco de complexión menuda por secuestro y extorsión, no le ha dado el acceso a la justicia. Pese a que logró hacer un retrato hablado de sus secuestradores y tres de ellos fueron detenidos, identificados y señalados por él, fueron liberados por “falta de pruebas”.

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Se autoriza su reproducción siempre y cuando se cite claramente al autor y la siguiente frase: “Este trabajo forma parte del proyecto En el Camino, realizado por la Red de Periodistas de a Pie con el apoyo de Open Society Foundations. Conoce más del proyecto aquí: enelcamino.periodistasdeapie.org.mx”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

During the last few years, the Mexican government has been bragging about numerous immigrants´ rescues. Once put in practice, those rescues become massive deportations, since the immigrants´ rights to justice and safety are not granted. Case to the point, less than 1% of the so called “rescued” immigrants during 2014 was granted a humanitarian visa.

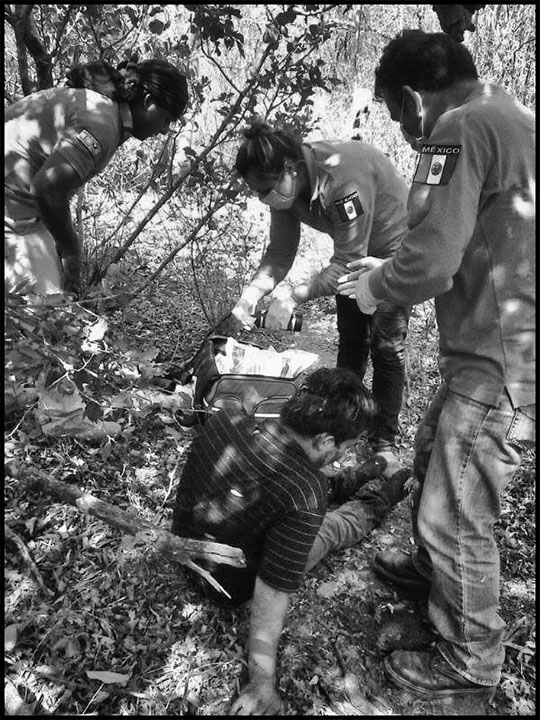

Text by: Mely Arellano, Ximena Natera, Jade Ramírez and Majo Siscar When she was kidnapped, Paola Quiñones didn’t get in touch with her family, the police or any other authority. The first place she called was the Hermanos del Camino immigrant shelter, under the care of Father Solalinde, in Ixtepec, Oaxaca. Her kidnappers requested a substantial ransom for each one of the immigrants stacked among several safe-houses, the priest managed to get a police raid to free them instead. The morning of June 23, 2014, came early in Reynosa. Attorney General´s Office (PGR) raided several houses based on the clues provided by Paola Quiñones until they found over a hundred immigrants, 114 according to Human Rights activists, among them Paola Quiñones and her friend Jorge Moncada. They had been held prisoners for 11 days, after being taken at gunpoint from the bus they were traveling on to the Tamaulipas-Texas border. They were taken to the Tamaulipas´ Attorney General´s office that same day, June 23rd, to file a complaint along with other 112 immigrants. They spent the night there, without a bed to sleep in, not even a blanket. The very next day they were taken to the Mexico City Attorney General´s Office, where they spent 3 more days. Then they were taken to Las Agujas immigration station in Iztapalapa, in the east side of Mexico City, where they started the paperwork to get them out of the country, without ever receiving any kind of aid or assistance. Almost all of the immigrants were deported during the following days. Immigrants, who have been victims of a crime within Mexico, have the right to denounce it and start a process to legalize their stay in the country through a humanitarian visa or political shelter, as stated in the Refugees and Political Asylum Migratory Laws. Nevertheless, in practice, Mexico´s government led by Enrique Peña Nieto, transgresses its own law and, the so called, “rescues” wind up being massive deportations and transgressions to the immigrants´ right to justice and safety. In this investigation, conducted by En el Camino based on information requests, follow up on kidnapping cases and interviews with human rights activists, we have unveiled something baptized as “masked detentions” by different organizations; due to the fact that the number of immigrants who were supposedly rescued matches the number of those who were later deported, besides the fact that less than 1% of the “rescued” immigrants during 2014, were able to obtain a humanitarian visa. [caption id="attachment_1663" align="aligncenter" width="720"] Paola Quiñones, a survivor.[/caption]

During the last few years, the Mexican government has been bragging about numerous immigrants´ rescues. Once put in practice, those rescues become massive deportations, since the immigrants´ rights to justice and safety are not granted. Case to the point, less than 1% of the so called “rescued” immigrants during 2014 was granted a humanitarian visa.

Text by: Mely Arellano, Ximena Natera, Jade Ramírez and Majo Siscar

When she was kidnapped, Paola Quiñones didn’t get in touch with her family, the police or any other authority. The first place she called was the Hermanos del Camino immigrant shelter, under the care of Father Solalinde, in Ixtepec, Oaxaca. Her kidnappers requested a substantial ransom for each one of the immigrants stacked among several safe-houses, the priest managed to get a police raid to free them instead.

The morning of June 23, 2014, came early in Reynosa. Attorney General´s Office (PGR) raided several houses based on the clues provided by Paola Quiñones until they found over a hundred immigrants, 114 according to Human Rights activists, among them Paola Quiñones and her friend Jorge Moncada.

They had been held prisoners for 11 days, after being taken at gunpoint from the bus they were traveling on to the Tamaulipas-Texas border. They were taken to the Tamaulipas´ Attorney General´s office that same day, June 23rd, to file a complaint along with other 112 immigrants. They spent the night there, without a bed to sleep in, not even a blanket. The very next day they were taken to the Mexico City Attorney General´s Office, where they spent 3 more days. Then they were taken to Las Agujas immigration station in Iztapalapa, in the east side of Mexico City, where they started the paperwork to get them out of the country, without ever receiving any kind of aid or assistance. Almost all of the immigrants were deported during the following days.

Immigrants, who have been victims of a crime within Mexico, have the right to denounce it and start a process to legalize their stay in the country through a humanitarian visa or political shelter, as stated in the Refugees and Political Asylum Migratory Laws.

Nevertheless, in practice, Mexico´s government led by Enrique Peña Nieto, transgresses its own law and, the so called, “rescues” wind up being massive deportations and transgressions to the immigrants´ right to justice and safety.

In this investigation, conducted by En el Camino based on information requests, follow up on kidnapping cases and interviews with human rights activists, we have unveiled something baptized as “masked detentions” by different organizations; due to the fact that the number of immigrants who were supposedly rescued matches the number of those who were later deported, besides the fact that less than 1% of the “rescued” immigrants during 2014, were able to obtain a humanitarian visa.

During the last few years, the Mexican government has been bragging about numerous immigrants´ rescues. Once put in practice, those rescues become massive deportations, since the immigrants´ rights to justice and safety are not granted. Case to the point, less than 1% of the so called “rescued” immigrants during 2014 was granted a humanitarian visa.

Text by: Mely Arellano, Ximena Natera, Jade Ramírez and Majo Siscar

When she was kidnapped, Paola Quiñones didn’t get in touch with her family, the police or any other authority. The first place she called was the Hermanos del Camino immigrant shelter, under the care of Father Solalinde, in Ixtepec, Oaxaca. Her kidnappers requested a substantial ransom for each one of the immigrants stacked among several safe-houses, the priest managed to get a police raid to free them instead.

The morning of June 23, 2014, came early in Reynosa. Attorney General´s Office (PGR) raided several houses based on the clues provided by Paola Quiñones until they found over a hundred immigrants, 114 according to Human Rights activists, among them Paola Quiñones and her friend Jorge Moncada.

They had been held prisoners for 11 days, after being taken at gunpoint from the bus they were traveling on to the Tamaulipas-Texas border. They were taken to the Tamaulipas´ Attorney General´s office that same day, June 23rd, to file a complaint along with other 112 immigrants. They spent the night there, without a bed to sleep in, not even a blanket. The very next day they were taken to the Mexico City Attorney General´s Office, where they spent 3 more days. Then they were taken to Las Agujas immigration station in Iztapalapa, in the east side of Mexico City, where they started the paperwork to get them out of the country, without ever receiving any kind of aid or assistance. Almost all of the immigrants were deported during the following days.

Immigrants, who have been victims of a crime within Mexico, have the right to denounce it and start a process to legalize their stay in the country through a humanitarian visa or political shelter, as stated in the Refugees and Political Asylum Migratory Laws.

Nevertheless, in practice, Mexico´s government led by Enrique Peña Nieto, transgresses its own law and, the so called, “rescues” wind up being massive deportations and transgressions to the immigrants´ right to justice and safety.

In this investigation, conducted by En el Camino based on information requests, follow up on kidnapping cases and interviews with human rights activists, we have unveiled something baptized as “masked detentions” by different organizations; due to the fact that the number of immigrants who were supposedly rescued matches the number of those who were later deported, besides the fact that less than 1% of the “rescued” immigrants during 2014, were able to obtain a humanitarian visa.

¿RESCATES O DEPORTACIONES?

Paola Quiñones, a survivor.[/caption]

During the last few years, the Mexican government has been bragging about numerous immigrants´ rescues. Once put in practice, those rescues become massive deportations, since the immigrants´ rights to justice and safety are not granted. Case to the point, less than 1% of the so called “rescued” immigrants during 2014 was granted a humanitarian visa.

Text by: Mely Arellano, Ximena Natera, Jade Ramírez and Majo Siscar

When she was kidnapped, Paola Quiñones didn’t get in touch with her family, the police or any other authority. The first place she called was the Hermanos del Camino immigrant shelter, under the care of Father Solalinde, in Ixtepec, Oaxaca. Her kidnappers requested a substantial ransom for each one of the immigrants stacked among several safe-houses, the priest managed to get a police raid to free them instead.

The morning of June 23, 2014, came early in Reynosa. Attorney General´s Office (PGR) raided several houses based on the clues provided by Paola Quiñones until they found over a hundred immigrants, 114 according to Human Rights activists, among them Paola Quiñones and her friend Jorge Moncada.

They had been held prisoners for 11 days, after being taken at gunpoint from the bus they were traveling on to the Tamaulipas-Texas border. They were taken to the Tamaulipas´ Attorney General´s office that same day, June 23rd, to file a complaint along with other 112 immigrants. They spent the night there, without a bed to sleep in, not even a blanket. The very next day they were taken to the Mexico City Attorney General´s Office, where they spent 3 more days. Then they were taken to Las Agujas immigration station in Iztapalapa, in the east side of Mexico City, where they started the paperwork to get them out of the country, without ever receiving any kind of aid or assistance. Almost all of the immigrants were deported during the following days.

Immigrants, who have been victims of a crime within Mexico, have the right to denounce it and start a process to legalize their stay in the country through a humanitarian visa or political shelter, as stated in the Refugees and Political Asylum Migratory Laws.

Nevertheless, in practice, Mexico´s government led by Enrique Peña Nieto, transgresses its own law and, the so called, “rescues” wind up being massive deportations and transgressions to the immigrants´ right to justice and safety.

In this investigation, conducted by En el Camino based on information requests, follow up on kidnapping cases and interviews with human rights activists, we have unveiled something baptized as “masked detentions” by different organizations; due to the fact that the number of immigrants who were supposedly rescued matches the number of those who were later deported, besides the fact that less than 1% of the “rescued” immigrants during 2014, were able to obtain a humanitarian visa.

During the last few years, the Mexican government has been bragging about numerous immigrants´ rescues. Once put in practice, those rescues become massive deportations, since the immigrants´ rights to justice and safety are not granted. Case to the point, less than 1% of the so called “rescued” immigrants during 2014 was granted a humanitarian visa.

Text by: Mely Arellano, Ximena Natera, Jade Ramírez and Majo Siscar

When she was kidnapped, Paola Quiñones didn’t get in touch with her family, the police or any other authority. The first place she called was the Hermanos del Camino immigrant shelter, under the care of Father Solalinde, in Ixtepec, Oaxaca. Her kidnappers requested a substantial ransom for each one of the immigrants stacked among several safe-houses, the priest managed to get a police raid to free them instead.

The morning of June 23, 2014, came early in Reynosa. Attorney General´s Office (PGR) raided several houses based on the clues provided by Paola Quiñones until they found over a hundred immigrants, 114 according to Human Rights activists, among them Paola Quiñones and her friend Jorge Moncada.

They had been held prisoners for 11 days, after being taken at gunpoint from the bus they were traveling on to the Tamaulipas-Texas border. They were taken to the Tamaulipas´ Attorney General´s office that same day, June 23rd, to file a complaint along with other 112 immigrants. They spent the night there, without a bed to sleep in, not even a blanket. The very next day they were taken to the Mexico City Attorney General´s Office, where they spent 3 more days. Then they were taken to Las Agujas immigration station in Iztapalapa, in the east side of Mexico City, where they started the paperwork to get them out of the country, without ever receiving any kind of aid or assistance. Almost all of the immigrants were deported during the following days.

Immigrants, who have been victims of a crime within Mexico, have the right to denounce it and start a process to legalize their stay in the country through a humanitarian visa or political shelter, as stated in the Refugees and Political Asylum Migratory Laws.

Nevertheless, in practice, Mexico´s government led by Enrique Peña Nieto, transgresses its own law and, the so called, “rescues” wind up being massive deportations and transgressions to the immigrants´ right to justice and safety.

In this investigation, conducted by En el Camino based on information requests, follow up on kidnapping cases and interviews with human rights activists, we have unveiled something baptized as “masked detentions” by different organizations; due to the fact that the number of immigrants who were supposedly rescued matches the number of those who were later deported, besides the fact that less than 1% of the “rescued” immigrants during 2014, were able to obtain a humanitarian visa.

¿RESCATES O DEPORTACIONES?

Ni la ley ni el reglamento de Migración define el término“rescate” o “rescatado”. Sin embargo, en sus boletines el INM lo utiliza para señalar que se liberó a migrantes de manos de traficantes, secuestradores o casas de seguridad o tráilers donde estaban en espera de cruzar a Estados Unidos.

La falta de acatamiento de la ley y del seguimiento jurídico a los migrantes “rescatados” impide distinguir cuándo se trata de migrantes que realmente estaban secuestrados y cuándo de quienes esperaban en casas de seguridad, hoteles o a bordo de camiones cruzar la frontera.

“(En algunos casos) Parece que la autoridad está engañando y en realidad está deteniendo a migrantes que esperan cruzar” alerta Córdova, desde el Consejo Ciudadano del INM.

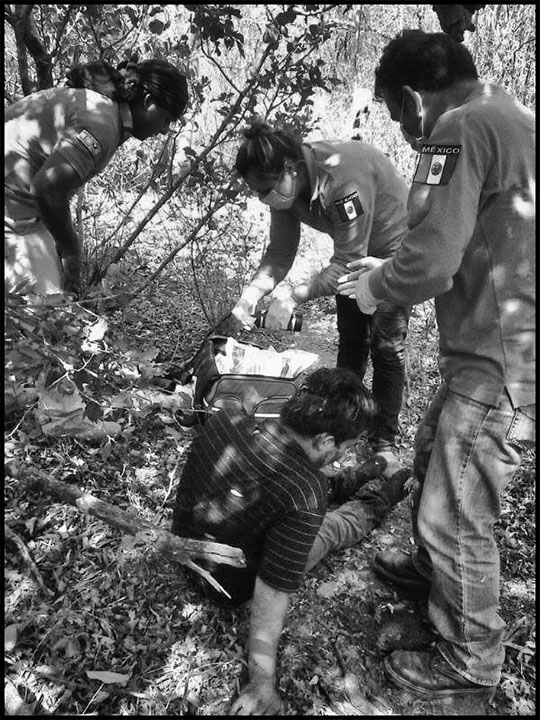

[caption id="attachment_1664" align="aligncenter" width="720"] National Migration Institute, harassment.[/caption]

On June 11th, when she got on that bus to the Tamaulipas-U.S. border, Paola didn’t think anything could happen to her. This time she was traveling on an official route, away from the vulnerability of the hideouts where undocumented immigrants have to stay. Organized crime doesn’t ask for documents, though.

Ten days after the Reynosa raid, Paola and Jorge managed to get out of the immigration station and settled in the CAFEMIN, a shelter run by the Scalabrinians Sisters. They started the official complaint for their kidnapping from there. They were able to do so, thanks to the assistance of an independent institution.

The other 112 immigrants, secured by the PGR and later put into INM´s custody, remained detained in the immigration station and, one by one, were sent back to their countries, after signing an, according to the authorities, “voluntary” deportation. This is legally known as “assisted repatriation”, though in practice it is a deportation that is not registered on the immigrant´s migratory record.

Someone who has just faced a traumatic experience needs a place to receive medical assistance and recover both psychologically and legally. However, the assisted repatriations are tainted by exhaustion, lack of psychological assistance and loss of hope among the victims, who cannot find an access to justice nor to be set free fast enough for them to resume their journey to the northern border.

“There wasn’t a single complaint filed by the immigrants being held by the INM. The institution wore them down and stalled them to keep them from starting a regularization legal process. The INM cornered them to sign their repatriation”, claims Alberto Donis.

“They break their hopes, they tell them: “you will remain detained for the duration of the process, so you better go, go back, we will pay for the bus, you will be fed, you ought to go back.” That is every day’s routine”, explains Leticia Gutierrez, Migrants and Refugees Scalabrinians Mission´s Director, A.K.A Sister Letty, who has played the role of mediator between civil organizations and the PGR regarding the issue of the immigrants who have been victims of a crime.

[caption id="attachment_1667" align="aligncenter" width="720"]

National Migration Institute, harassment.[/caption]

On June 11th, when she got on that bus to the Tamaulipas-U.S. border, Paola didn’t think anything could happen to her. This time she was traveling on an official route, away from the vulnerability of the hideouts where undocumented immigrants have to stay. Organized crime doesn’t ask for documents, though.

Ten days after the Reynosa raid, Paola and Jorge managed to get out of the immigration station and settled in the CAFEMIN, a shelter run by the Scalabrinians Sisters. They started the official complaint for their kidnapping from there. They were able to do so, thanks to the assistance of an independent institution.

The other 112 immigrants, secured by the PGR and later put into INM´s custody, remained detained in the immigration station and, one by one, were sent back to their countries, after signing an, according to the authorities, “voluntary” deportation. This is legally known as “assisted repatriation”, though in practice it is a deportation that is not registered on the immigrant´s migratory record.

Someone who has just faced a traumatic experience needs a place to receive medical assistance and recover both psychologically and legally. However, the assisted repatriations are tainted by exhaustion, lack of psychological assistance and loss of hope among the victims, who cannot find an access to justice nor to be set free fast enough for them to resume their journey to the northern border.

“There wasn’t a single complaint filed by the immigrants being held by the INM. The institution wore them down and stalled them to keep them from starting a regularization legal process. The INM cornered them to sign their repatriation”, claims Alberto Donis.

“They break their hopes, they tell them: “you will remain detained for the duration of the process, so you better go, go back, we will pay for the bus, you will be fed, you ought to go back.” That is every day’s routine”, explains Leticia Gutierrez, Migrants and Refugees Scalabrinians Mission´s Director, A.K.A Sister Letty, who has played the role of mediator between civil organizations and the PGR regarding the issue of the immigrants who have been victims of a crime.

[caption id="attachment_1667" align="aligncenter" width="720"] Solalinde, a tireless battle on behalf of immigrants[/caption]

Victims without a Humanitarian Visa

Those immigrants had the right to regularize their stay in the country, due to the fact they had been victims of a crime. As a matter of fact, Paola Quiñones had already started the paper work to regularize her stay when she arrived to Father Solalinde´s shelter. Barely a few months earlier, in Tuxtla Gutierrez, Chiapas, three policemen attacked her and stole all of her money and belongings under the threat of taking her to the INM´s office. When she finally arrived to Ixtepec, the priest and Donis encouraged her to file a denouncement. Once she got her file, she started the paperwork to get her visa.

En el Camino requested through INFOMEX “details about rescue, salvage and securement operations of immigrants since January the 1st 2008 to February 2015”. The information delivered started in 2012, when the new Immigration Law was implemented.

According to the official data (delivered under the request # 0411100011515), from 2008 to 2015, 84500 operatives have been performed using checkpoints spread among Mexico City and the 29 states (some of them delivered the information in an illegible or incomplete format: Aguascalientes, Durango, Veracruz, Baja California Sur and Sinaloa). Among all of them, the authorities acknowledge only 427 people as “possible crime victims”.

This would mean, only one immigrant out of 200 “rescue” operations, would have faced violence. The numbers delivered unveil a brutal difference between “rescued” immigrants and those acknowledged as “victims”.

“If the 127,000 rescued immigrants, mentioned by Ardelio Vargas (INM´s commissioner), were snatched from the claws of the organized crime, we should be issuing thousands of humanitarian visas”, ponders Cordoba.

According to Sister Leticia, when an immigrant is victim of a crime, despite the fact they can choose not to file a complaint, most of them actually do if they are properly assisted. Her organization aided, only during the first 6 months in 2015, 189 victims, only 10 of them decided not to denounce the crime.

[caption id="attachment_1665" align="aligncenter" width="720"]

Solalinde, a tireless battle on behalf of immigrants[/caption]

Victims without a Humanitarian Visa

Those immigrants had the right to regularize their stay in the country, due to the fact they had been victims of a crime. As a matter of fact, Paola Quiñones had already started the paper work to regularize her stay when she arrived to Father Solalinde´s shelter. Barely a few months earlier, in Tuxtla Gutierrez, Chiapas, three policemen attacked her and stole all of her money and belongings under the threat of taking her to the INM´s office. When she finally arrived to Ixtepec, the priest and Donis encouraged her to file a denouncement. Once she got her file, she started the paperwork to get her visa.

En el Camino requested through INFOMEX “details about rescue, salvage and securement operations of immigrants since January the 1st 2008 to February 2015”. The information delivered started in 2012, when the new Immigration Law was implemented.

According to the official data (delivered under the request # 0411100011515), from 2008 to 2015, 84500 operatives have been performed using checkpoints spread among Mexico City and the 29 states (some of them delivered the information in an illegible or incomplete format: Aguascalientes, Durango, Veracruz, Baja California Sur and Sinaloa). Among all of them, the authorities acknowledge only 427 people as “possible crime victims”.

This would mean, only one immigrant out of 200 “rescue” operations, would have faced violence. The numbers delivered unveil a brutal difference between “rescued” immigrants and those acknowledged as “victims”.

“If the 127,000 rescued immigrants, mentioned by Ardelio Vargas (INM´s commissioner), were snatched from the claws of the organized crime, we should be issuing thousands of humanitarian visas”, ponders Cordoba.

According to Sister Leticia, when an immigrant is victim of a crime, despite the fact they can choose not to file a complaint, most of them actually do if they are properly assisted. Her organization aided, only during the first 6 months in 2015, 189 victims, only 10 of them decided not to denounce the crime.

[caption id="attachment_1665" align="aligncenter" width="720"] Ixtepec, Oaxaca, longing for a humanitarian visa.[/caption]

The En el Camino team researched the number of humanitarian visas issued since 2012 through INAI (request #0411100011515). However, the authority did not acknowledged to have granted any.

From the information provided we learned that in 314 cases an exit letter could have been provided. That is a permit to leave the country legally within 30 days. We use the conditional “could have” because the answer was broken down by the number of operations and not by particular cases, therefore an operation where 12 people were “rescued” there could have been 3 “victims of a crime”, but INM only reports what happened with the 12people in total, not with the 3 victims.

The fact we are positive about, is that at least 113 out of those 427 “possible” victims of a crime were sent back to their home countries, either via deportation or assisted repatriation.

From its side, the Unidad de Politica Migratoria (Migratory Policies Unit) does not have a record about how many humanitarian visas had been issued before 2013, but they do starting 2014. On that year it is reported 623 humanitarian visas were granted, a meager number compared to the 127,149 immigrants who, according to that same institution, were rescued during 2014, which means that humanitarian visas were granted to only 0.4% of the immigrants who were “rescued”. From the total number, according to the records, 107,814 were sent back to their home countries and the rest, over 18,000 cases, show no information.

During the first months of 2015, 527 humanitarian visas were granted, however, 97,513 immigrants were “rescued” and 82,266 were “sent back”. The percentage of humanitarian visas granted was also under 1%.

Without Humanitarian Assistance

In June 2014, after the 114 immigrants were taken to Las Agujas, in Iztapalapa, Father Solalinde and one of his collaborators, Alberto Donis arrived, moved by Paola Quiñones´ call. The priest had a doctor to look at Paola and Jorge; he found them suffering of severe infections, dehydrated and malnourished. They were both feeble and suffering post-traumatic stress as a consequence of the kidnapping.

“It was very difficult for me, we didn’t receive the assistance we deserved and needed. There was no medical assistance, leave alone psychological. We didn’t know what was going on”, states Quiñones from Honduras, where she visits her family.

Inside Las Agujas, there are prison cells, punishment cells and even a mob, formed by the inmates, that controls the cigarettes and food trade as well as the phone rights, as denounced by the organization Sin Fronteras. Although there isn’t budget to ensure health care and the minimum attentions necessary to someone who has suffered kidnapping or any other serious crime.

[caption id="attachment_1666" align="aligncenter" width="720"]

Ixtepec, Oaxaca, longing for a humanitarian visa.[/caption]

The En el Camino team researched the number of humanitarian visas issued since 2012 through INAI (request #0411100011515). However, the authority did not acknowledged to have granted any.

From the information provided we learned that in 314 cases an exit letter could have been provided. That is a permit to leave the country legally within 30 days. We use the conditional “could have” because the answer was broken down by the number of operations and not by particular cases, therefore an operation where 12 people were “rescued” there could have been 3 “victims of a crime”, but INM only reports what happened with the 12people in total, not with the 3 victims.

The fact we are positive about, is that at least 113 out of those 427 “possible” victims of a crime were sent back to their home countries, either via deportation or assisted repatriation.

From its side, the Unidad de Politica Migratoria (Migratory Policies Unit) does not have a record about how many humanitarian visas had been issued before 2013, but they do starting 2014. On that year it is reported 623 humanitarian visas were granted, a meager number compared to the 127,149 immigrants who, according to that same institution, were rescued during 2014, which means that humanitarian visas were granted to only 0.4% of the immigrants who were “rescued”. From the total number, according to the records, 107,814 were sent back to their home countries and the rest, over 18,000 cases, show no information.

During the first months of 2015, 527 humanitarian visas were granted, however, 97,513 immigrants were “rescued” and 82,266 were “sent back”. The percentage of humanitarian visas granted was also under 1%.

Without Humanitarian Assistance

In June 2014, after the 114 immigrants were taken to Las Agujas, in Iztapalapa, Father Solalinde and one of his collaborators, Alberto Donis arrived, moved by Paola Quiñones´ call. The priest had a doctor to look at Paola and Jorge; he found them suffering of severe infections, dehydrated and malnourished. They were both feeble and suffering post-traumatic stress as a consequence of the kidnapping.

“It was very difficult for me, we didn’t receive the assistance we deserved and needed. There was no medical assistance, leave alone psychological. We didn’t know what was going on”, states Quiñones from Honduras, where she visits her family.

Inside Las Agujas, there are prison cells, punishment cells and even a mob, formed by the inmates, that controls the cigarettes and food trade as well as the phone rights, as denounced by the organization Sin Fronteras. Although there isn’t budget to ensure health care and the minimum attentions necessary to someone who has suffered kidnapping or any other serious crime.

[caption id="attachment_1666" align="aligncenter" width="720"] Immigrants, completely vulnerable in Mexico[/caption]

“Those immigrants, according to the law, should have been sent to special government shelters, since they are victims who are about to start a legal process. They are not detained, but they are left in the station without support or possibility to leave”, explains Alberto Donis who, besides Father Solalinde, attempted to negotiate the transferring of the 114 immigrants to Ixtepec. Due to the lack of resources their attempt was unsuccessful.

INM´s communication department (National Migration Institute) assured to En el Camino via telephone, that there is an internal mandate to assist immigrants who are looking to legalize their stay after being either victims or witnesses of a crime and that here, in Mexico, the survival and wellbeing of immigrants are provided. Nevertheless, according to the “Detention, Identification and Assistance of foreign victims of a crime Procedure”, a protocol detailing the scope of the migratory authorities contained in the Migratory Law, the victims of a crime “will be directed to an institution, public or private, to receive the required assistance” and, regarding victims of human trafficking, “their stay in shelters and specialized institutions will be guaranteed”.

However, Paola Quiñones and the rest of the “rescued” immigrants were not offered a place in any institution nor money to survive for the duration of the process. Only Solalinde´s shelter allowed her to stay for three months, in exchange for her cooking in the shelter´s diner.

Leticia Gutierrez states that the lack of follow up on the victims of a crime is such that there isn’t data to obtain patterns, hence preventing future kidnappings.

[caption id="attachment_21" align="aligncenter" width="540"]

Immigrants, completely vulnerable in Mexico[/caption]

“Those immigrants, according to the law, should have been sent to special government shelters, since they are victims who are about to start a legal process. They are not detained, but they are left in the station without support or possibility to leave”, explains Alberto Donis who, besides Father Solalinde, attempted to negotiate the transferring of the 114 immigrants to Ixtepec. Due to the lack of resources their attempt was unsuccessful.

INM´s communication department (National Migration Institute) assured to En el Camino via telephone, that there is an internal mandate to assist immigrants who are looking to legalize their stay after being either victims or witnesses of a crime and that here, in Mexico, the survival and wellbeing of immigrants are provided. Nevertheless, according to the “Detention, Identification and Assistance of foreign victims of a crime Procedure”, a protocol detailing the scope of the migratory authorities contained in the Migratory Law, the victims of a crime “will be directed to an institution, public or private, to receive the required assistance” and, regarding victims of human trafficking, “their stay in shelters and specialized institutions will be guaranteed”.

However, Paola Quiñones and the rest of the “rescued” immigrants were not offered a place in any institution nor money to survive for the duration of the process. Only Solalinde´s shelter allowed her to stay for three months, in exchange for her cooking in the shelter´s diner.

Leticia Gutierrez states that the lack of follow up on the victims of a crime is such that there isn’t data to obtain patterns, hence preventing future kidnappings.

[caption id="attachment_21" align="aligncenter" width="540"] Click to learn about the Guatemalan man who survived a machete attack[/caption]

“INM´s speech is intended to convince the general public, however, the biggest problem is that, whenever they actually issue humanitarian visas, 90% of the cases is because a shelter assisted the requestor for the duration of the process. Nobody gets documents from within the INM”, concludes Donis. While deportations and assisted repatriations continue, the complaint filed by the worn out Guatemalan man after being kidnapped and blackmailed, has given him no access to justice. Despite the fact he provided a physical description and a sketch of his kidnappers, which led to the arrest of three of them, after being positively identified, they were released due to “lack of evidence”.

Click to learn about the Guatemalan man who survived a machete attack[/caption]

“INM´s speech is intended to convince the general public, however, the biggest problem is that, whenever they actually issue humanitarian visas, 90% of the cases is because a shelter assisted the requestor for the duration of the process. Nobody gets documents from within the INM”, concludes Donis. While deportations and assisted repatriations continue, the complaint filed by the worn out Guatemalan man after being kidnapped and blackmailed, has given him no access to justice. Despite the fact he provided a physical description and a sketch of his kidnappers, which led to the arrest of three of them, after being positively identified, they were released due to “lack of evidence”.

Reproduction is authorized as long as the author, the text and the following are clearly quoted “This article is part of the project En el Camino, produced by Red de Periodistas de a Pie with the support of Open Society Foundations. To find out more about this project visit: enelcamino.periodistasdeapie.org.mx”